|

John Bellardo and Stefan Savage

Department of Computer Science and Engineering

University of California at San Diego

In contrast, this paper focuses on the threats posed by denial-of-service (DoS) attacks against 802.11's MAC protocol. Such attacks, which prevent legitimate users from accessing the network, are a vexing problem in all networks, but they are particularly threatening in the wireless context. Without a physical infrastructure, an attacker is afforded considerable flexibility in deciding where and when to attack, as well as enhanced anonymity due to the difficulty in locating the source of individual wireless transmissions. Moreover, the relative immaturity of 802.11-based network management tools makes it unlikely that a well-planned attack will be quickly diagnosed. Finally, as we will show, vulnerabilities in the 802.11 MAC protocol allow an attacker to selectively or completely disrupt service to the network using relatively few packets and low power consumption.

This paper makes four principal contributions. First, we provide a description of vulnerabilities in the 802.11 management and media access services that are vulnerable to attack. Second, we demonstrate that all such attacks are practical to implement by circumventing the normal operation of the firmware in commodity 802.11 devices. Third, we implement two important classes of denial-of-service attacks and investigate the range of their practical effectiveness. Finally, we describe, implement and evaluate non-cryptographic countermeasures that can be implemented in the firmware of existing MAC hardware.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 describes related security research conducted by others in academia, as well as unpublished, but contemporaneous, work from the ``blackhat'' security community. Section 3 describes and categorizes existing denial-of-service vulnerabilities in 802.11's MAC protocol. In Section 4 we use live experiments and simulation to analyze the practicality and efficacy of these attacks, followed by an evaluation of low-overhead countermeasures to mitigate the underlying vulnerabilities. Finally, we summarize our findings in Section 5.

While these works comprise the best known body of 802.11 security research, there has also been some attention focused on denial-of-service vulnerabilities unique to 802.11. As part of his PhD thesis, Lough identifies a number of security vulnerabilities in the 802.11 MAC protocol, including those that lead to the deauthentication/disassociation and virtual carrier-sense attacks presented in this paper [Lou01]. However, while Lough's thesis identifies these vulnerabilities, it does not validate them empirically. We demonstrate that such validation is critical to assessing the true threat of such attacks.

In addition to Lough's work, Faria and Cheriton consider the problems posed by authentication DoS attacks. They identify those assumption violations that lead to the vulnerabilities and propose a new authentication framework to address the problems [FC02]. Unlike their work, this paper focuses on validating the impact of the attacks and developing light-weight solutions that do not require significant changes to existing standards or extensive use of cryptography.

The deauthentication/disassociation attack is fairly straightforward to implement and while writing this paper we discovered several in the ``black hat'' community who had done so before us. Lacking publication dates it is difficult to determine the ordering of these efforts, but we are aware of three implementations to date: one by Baird and Lynn (AirJack) presented at BlackHat Briefings in July of 2002, another due to Schiffman and presented at the same event (Omerta), and a tool by Floeter (void11) that appears to be roughly contemporaenous [LB02,Sch02,Flo02]. As part of his implementation, Schiffman also discusses a general purpose toolkit, called Radiate, for injecting raw 802.11 frames into the channel. However, since this toolkit works through the firmware it is only able to generate a subset of legitimate 802.11 frames. Compared to this previous work, our contribution lies in evaluating the impact of the attack, providing a cheap means to mitigate such attacks and in providing an infrastructure for mounting a wider class of attacks (including the virtual carrier-sense attack).

Congestion-based MAC layer denial of service attacks have also been studied previously. Gupta et al. examined DoS attacks in 802.11 ad hoc networks and show that traditional wireline-based detection and prevention approaches do not work, and propose the use of MAC layer fairness to mitigate the problem [GKF02]. Kyasanur and Vaidya also look at congestion-based MAC DoS attacks, but from a general 802.11 prospective, not the purely ad hoc prospective [KV03]. They propose a straightforward method for detecting such attacks. In addition they propose and simulate a defense where uncompromised nodes cooperate to control the frame rate at the compromised node. Compared to these papers, we focus on attacks on the 802.11 MAC protocol itself rather than pure resource consumption attacks.

Finally, to provide a long-term solution to 802.11's security problems, the 802.11 TGi working group has proposed the standard use of the 802.1X protocol [IEE01] for authentication in future versions of 802.11 products, in addition to both short-term and long-term modifications to the privacy functions. However, while the working group is clearly aware of threats from unauthenticated management frames and spoofed control frames (e.g., [Abo02,Moo02]), to the best of our knowledge there is no protection against such attacks in the current drafts under discussion.

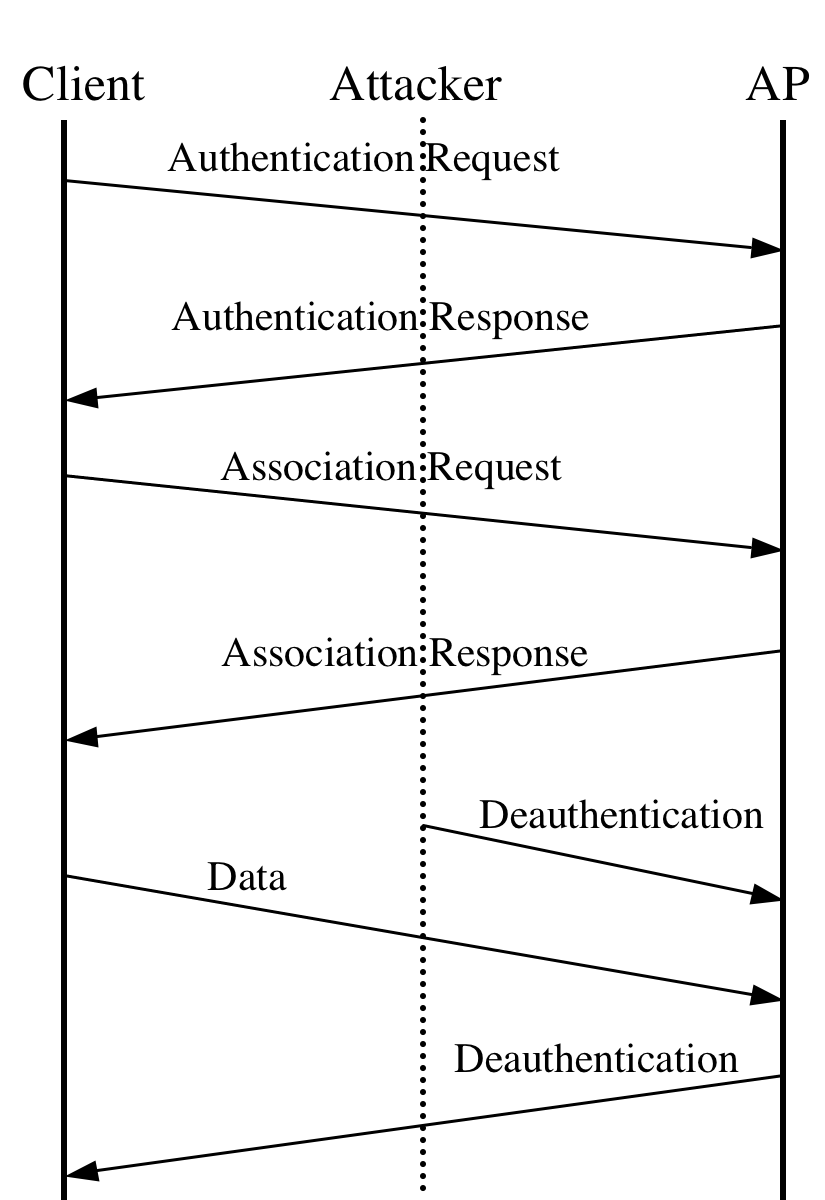

Exemplifying this problem is the deauthentication attack. After an 802.11 client has selected an access point to use for communication, it must first authenticate itself to the AP before further communication may commence. Moreover, part of the authentication framework is a message that allows clients and access points to explicitly request deauthentication from one another. Unfortunately, this message itself is not authenticated using any keying material. Consequently the attacker may spoof this message, either pretending to be the access point or the client, and direct it to the other party (see Figure 1). In response, the access point or client will exit the authenticated state and will refuse all further packets until authentication is reestablished. How long reestablishment takes is a function of how aggressively the client will attempt to reauthenticate and any higher-level timeouts or backoffs that may suppress the demand for communication. By repeating the attack persistently a client may be kept from transmitting or receiving data indefinitely.

One of the strengths of this attack is its great flexibility: an attacker may elect to deny access to individual clients, or even rate limit their access, in addition to simply denying service to the entire channel. However, accomplishing these goals efficiently requires the attacker to promiscuously monitor the channel and send deauthentication messages only when a new authentication has successfully taken place (indicated by the client's attempt to associate with the access point). As well, to prevent a client from ``escaping'' to a neighboring access point, the attacker must periodically scan all channels to ensure that the client has not switched to another overlapping access point.

|

Along the same vein, it is potentially possible to trick the client node into thinking there are no buffered packets at the access point when in fact there are. The presence of buffered packets is indicated in a periodically broadcast packet called the traffic indication map, or TIM. If the TIM message itself is spoofed, an attacker may convince a client that there is no pending data for it and the client will immediately revert back to the sleep state.

Finally, the power conservation mechanisms rely on time synchronization between the access point and its clients so clients know when to awake. Key synchronization information, such as the period of TIM packets and a timestamp broadcast by the access point, are sent unauthenticated and in the clear. By forging these management packets, an attacker can cause a client node to fall out of sync with the access point and fail to wake up at the appropriate times.

While all of the vulnerabilities in this section could be resolved with appropriate authentication of all messages, it seems unlikely that such a capability will emerge soon. With an installed base of over 15 million legacy 802.11 devices, the enormous growth of the public-area wireless access market and the managerial burden imposed by the shared key management of 802.1X, it seems unlikely that there will be universal deployment of mutual authentication infrastructure any time soon. Moreover, it is not clear whether future versions of the 802.11 specification will protect management frames such as deauthentication (while it is clear they are aware of the problem, the current work of the TGi working group still leaves the deauthentication operation unprotected).

|

802.11 networks go through significant effort to avoid transmit collisions. Due to hidden terminals perfect collision detection is not possible and a combination of physical carrier-sense and virtual carrier-sense mechanisms are employed in tandem to control access to the channel [BDSZ94]. Both of these mechanisms may be exploited by an attacker.

First, to prioritize access to the radio medium four time windows are defined. For the purposes of this discussion only two are important: the Short Interframe Space (SIFS) and the longer Distributed Coordination Function Interframe Space (DIFS). Before any frame can be sent the sending radio must observe a quiet medium for one of the defined window periods. The SIFS window is used for frames sent as part of a preexisting frame exchange (for example, the explicit ACK frame sent in response to a previously transmitted data frame). The DIFS window is used for nodes wishing to initiate a new frame exchange. To avoid all nodes transmitting immediately after the DIFS expires, the time after the DIFS is subdivided into slots. Each transmitting node randomly and with equal probability picks a slot in which to start transmitting. If a collision does occur (indicated implicitly by the lack of an immediate acknowledgment), the sender uses a random exponential backoff algorithm before retransmitting.

Since every transmitting node must wait at least an SIFS interval, if not longer, an attacker may completely monopolize the channel by sending a short signal before the end of every SIFS period. While this attack would likely be highly effective, it also requires the attacker to expend considerable energy. A SIFS period is only 20 microseconds on 802.11b networks, leading to a duty cycle of 50,000 packets per second in order to disable all access to the network.

A more serious vulnerability arises from the virtual carrier-sense mechanism used to mitigate collisions from hidden terminals. Each 802.11 frame carries a Duration field that indicates the number of microseconds that the channel is reserved. This value, in turn, is used to program the Network Allocation Vector (NAV) on each node. Only when a node's NAV reaches 0 is it allowed to transmit. This feature is principally used by the explicit request to send (RTS) / clear to send (CTS) handshake that can be used to synchronize access to the channel when a hidden terminal may be interfering with transmissions.

During this handshake the sending node first sends a small RTS frame that includes a duration large enough to complete the RTS/CTS sequence - including the CTS frame, the data frame, and the subsequent acknowledgment frame. The destination node replies to the RTS with a CTS, containing a new duration field updated to account for the time already elapsed during the sequence. After the CTS is sent, every node in radio range of either the sending or receiving node will have updated their NAV and will defer all transmissions for the duration of the future transaction. While the RTS/CTS feature is rarely used in practice, respecting the virtual carrier-sense function indicated by the duration field is mandatory in all 802.11 implementations.

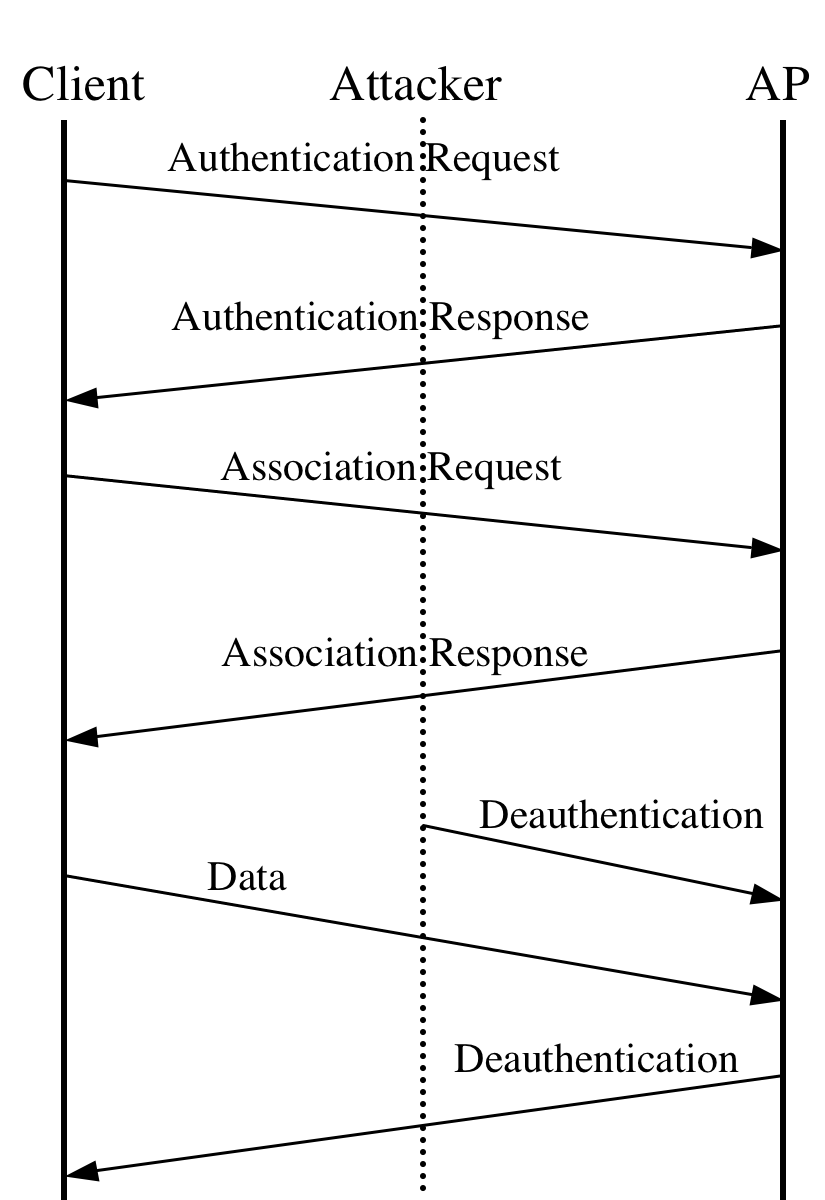

An attacker may exploit this feature by asserting a large duration field, thereby preventing well-behaved clients from gaining access to the channel (as shown in Figure 2). While it is possible to use almost any frame type to control the NAV, including an ACK, using the RTS has some advantages. Since a well-behaved node will always respond to RTS with a CTS, an attacker may co-opt legitimate nodes to propagate the attack further than it could on its own. Moreover, this approach allows an attacker to transmit with extremely low power or using a directional antennae, thereby reducing the probability of being located.

The maximum value for the NAV is 32767, or roughly 32 milliseconds on 802.11b networks, so in principal an attacker need only transmit approximately 30 times a second to jam all access to the channel. Finally, it is worth noting that RTS, CTS and ACK frames are not authenticated in any current or upcoming 802.11 standard. However, even if they were authenticated, this would only provide non-repudiation since, by design, the virtual-carrier sense feature impacts all nodes on the same channel.

At first glance this appears to be a trivial problem since all 802.11 Network Interface Cards (NIC) are inherently able to generate arbitrary frames. However, in practice, all 802.11(a,b) devices we are aware of implement key MAC functions in firmware and moderate access to the radio through a constrained interface. The implementation of this firmware, in turn, dictates the limits of how a NIC can be used by an attacker. Indeed, in reviewing preprints of this paper, several 802.11 experts declared the virtual carrier-sense attack infeasible in practice due to such limitations.

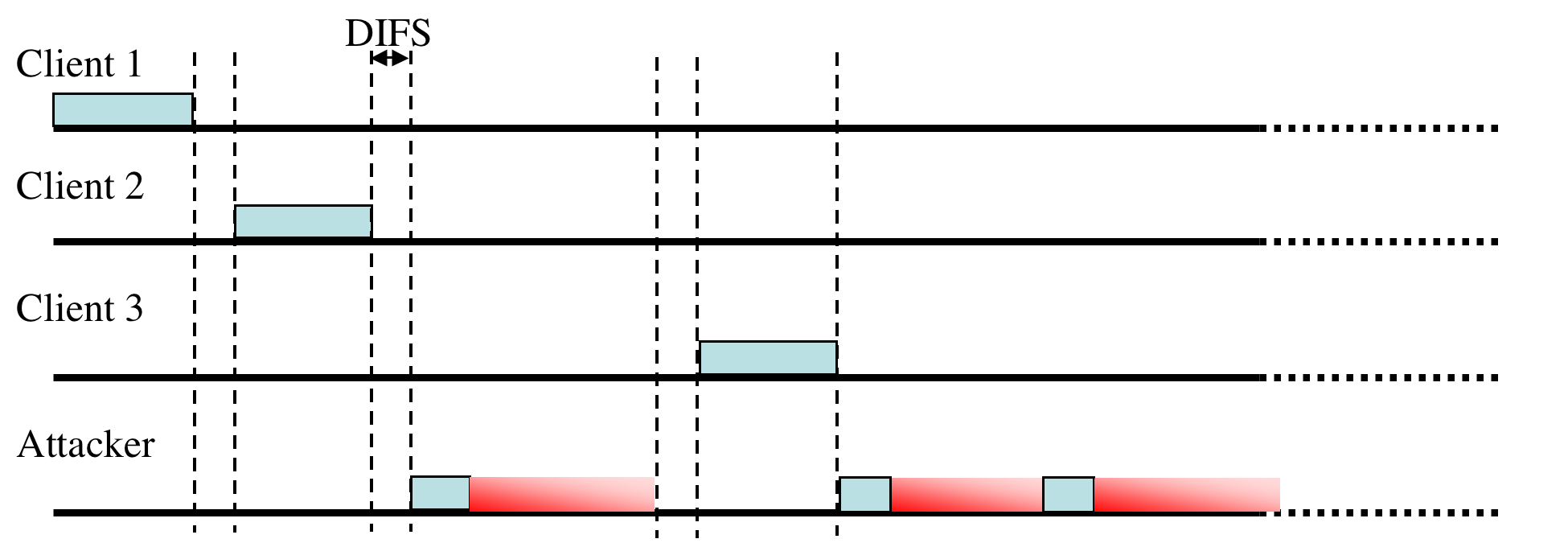

In testing a wide variety of 802.11 NICs we have found that most allow the generation of management frames necessary to exploit the identity attacks described earlier - typically using semi-documented or undocumented modes of operation, such as HostAP and HostBSS mode in Intersil firmware. However, these same devices do not typically allow the generation of any control frames, permit other key fields (such as Duration and FCS) to be specified by the host, or allow reserved or illegal field values to be transmitted. Instead, the firmware overwrites these fields with appropriate values after the host requests that queued data be transmitted. While it might be possible to reverse-engineer the firmware to remove this limitation, we believe the effort to do so would be considerable. Instead, we have developed an alternative mechanism to sidestep the limitations imposed by the firmware interface. To understand our approach it is first necessary to understand the architecture of existing 802.11 products.

|

However, Choice-based MACs also provide an unbuffered, unsychronized raw memory access interface for debug purposes - typically called the ``aux port''. By properly configuring the host and NIC, it is possible to write a frame via the BAP interface, locate it in the NIC's SRAM, request a transmission, and then modify the packet via the aux port - after the firmware has processed it, but before it is actually transmitted. This process is depicted in Figure 3. To synchronize the host and NIC, a simple barrier can be implemented by spinning on an 802.11 header field (such as duration) that is overwritten by the firmware. Alternatively, the host can continuously overwrite if synchronization is unnecessary. In practice, this ``data race'' approach, while undeniably ugly, is both reliable and permits the generation of arbitrary 802.11 MAC frames. Using this method we are able to implement any of the attacks previously described using off-the-shelf hardware. We believe we are the first to demonstrate this capability using commodity equipment.

|

To experiment with denial-of-service attacks we have built a demonstration application that passively monitors wireless channels for APs and clients. Individual clients are identified initially by their MAC address, but as they generate traffic, a custom DNS resolver and a slightly modified version of dsniff [Son] is used to isolate better identifiers (e.g., userids, DNS address of IMAP server, etc). These identifiers can be used to select individual hosts for attack, or all hosts may be attacked en masse. The application and the actual device are pictured in Figure 4.

In the remainder of this section, we analyze the impact of the deauthentication attack and a preliminary defense mechanism, followed by a similar examination of the virtual carrier-sense attack and defense.

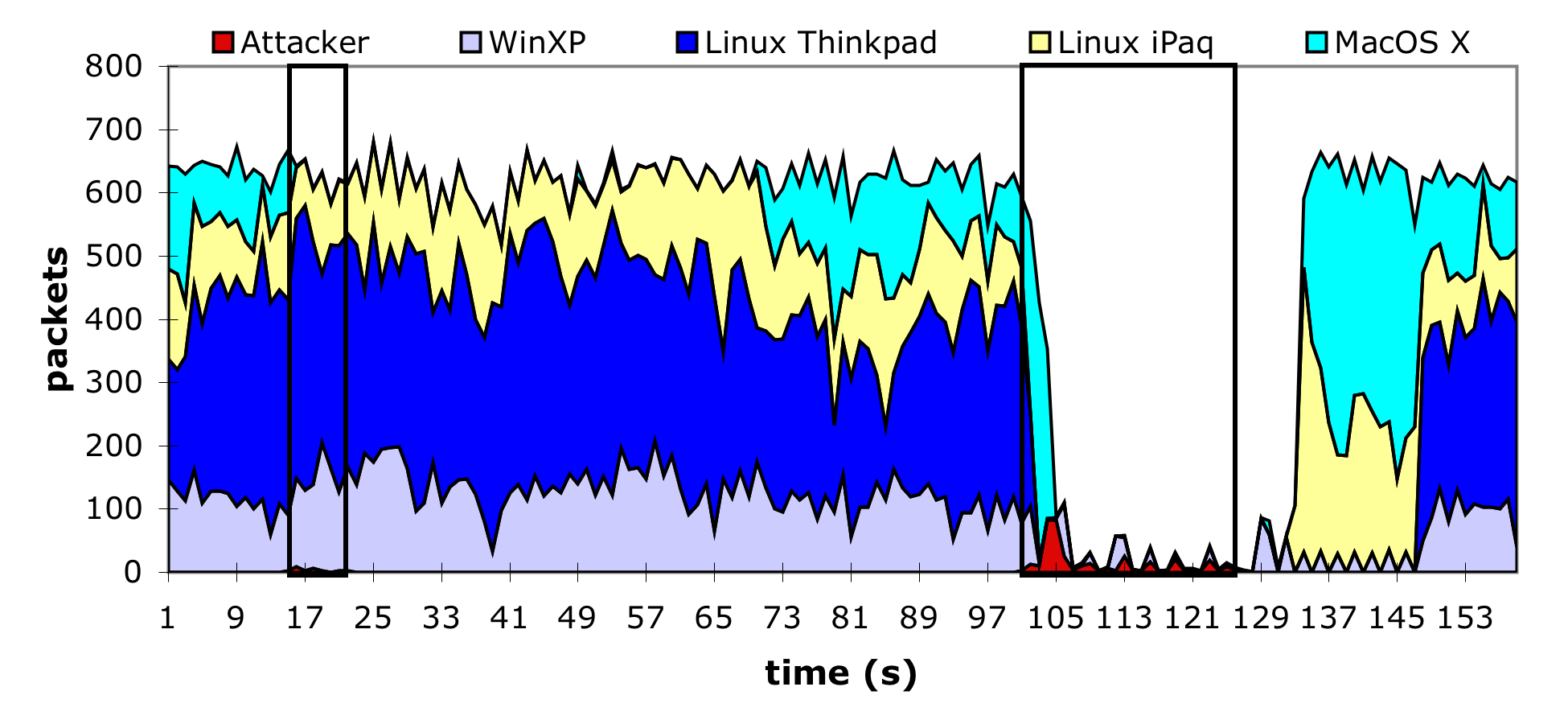

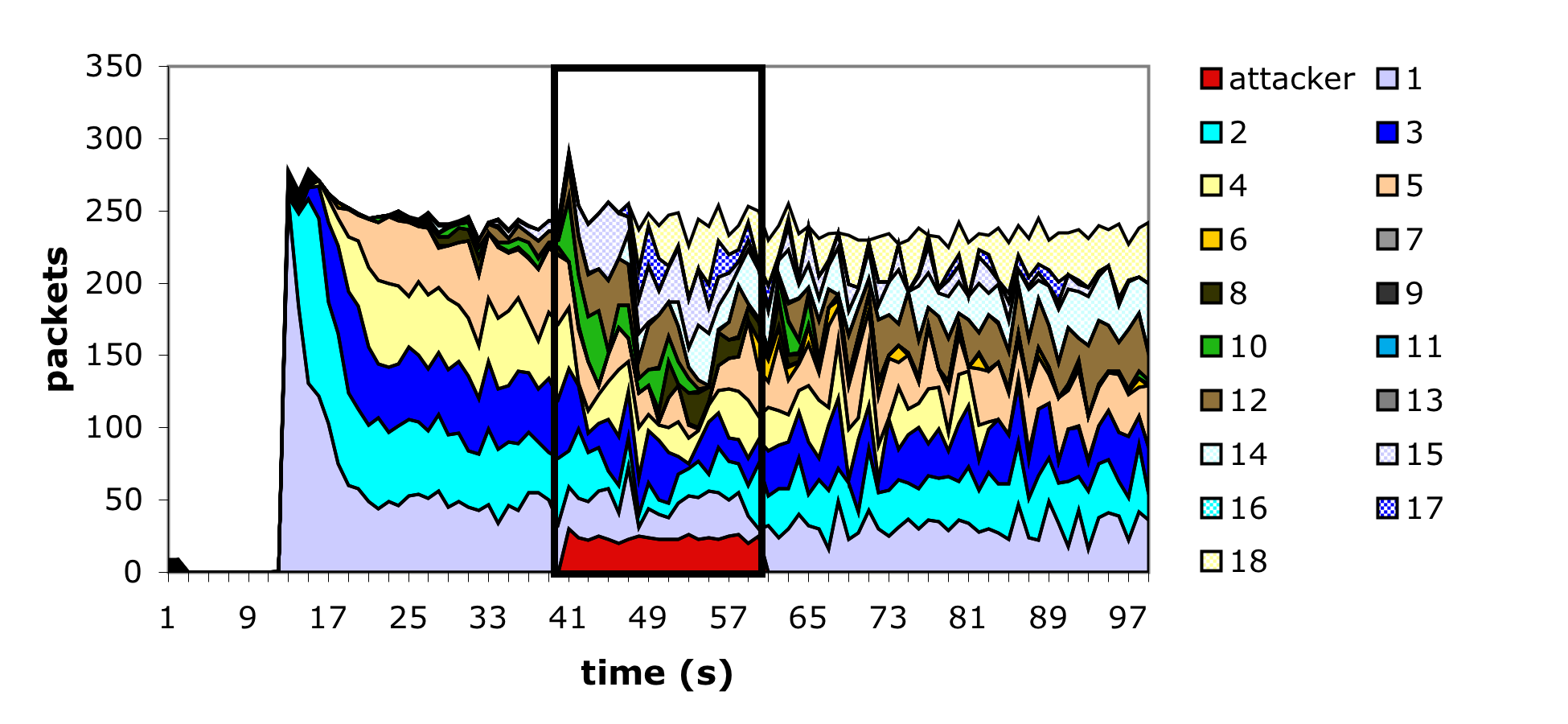

We tested this implementation in a small 802.11 network composed of 7 machines: 1 attacker, 1 access point, 1 monitoring station, and 4 legitimate clients. The access point was built using the Linux HostAP driver, which provides an in-kernel software-based access point. Each of the clients attempted to transfer, via ftp, a large file through the access point machine - a transfer which exceeded the testing period. We mounted two attacks on the network. The first, illustrated by the thin rectangle in Figure 5, was directed against a single client running MacOS X. This client's transfer was immediately halted, and even though the attack lasted less than ten seconds, the client did not resume transmitting at its previous rate for more than a minute. This amplification was due to a combination of an extended delay while the client probed for other access points and the exponential backoff being employed by the ftp server's TCP implementation.

|

A number of smaller, directed attacks were performed in addition to those in Figure 5. The small tests were done using the extended 802.11 infrastructure found at UCSD with varied victims. Recent versions of Windows, Linux, and the MacOS all gave up on the targeted access point and kept trying to find others. Slightly older versions of the same systems never attempted to switch access points and were completely disconnected using the less sophisticated version of the attack. The attack even caused one device, an HP Jornada Pocket PC, to consistently crash.

The deauthentication vulnerability can be solved directly by explicitly authenticating management frames and dropping invalid requests. However, the standardization of such capabilities is still some ways off and it is clear that legacy MAC designs do not have sufficient CPU capacity to implement this functionality as a software upgrade. Therefore, system-level defenses with low-overhead can still offer significant value. In particular, by delaying the effects of deauthentication or disassociation requests (e.g., by queuing such requests for 5-10 seconds) an AP has the opportunity to observe subsequent packets from the client. If a data packet arrives after a deauthentication or disassociation request is queued, that request is discarded - since a legitimate client would never generate packets in that order. The same approach can be used in reverse to mitigate forged deauthentication packets sent to the client on behalf of the AP. This approach has the advantage that it can be implemented with a simple firmware modification to existing NICs and access points, without requiring a new management structure.

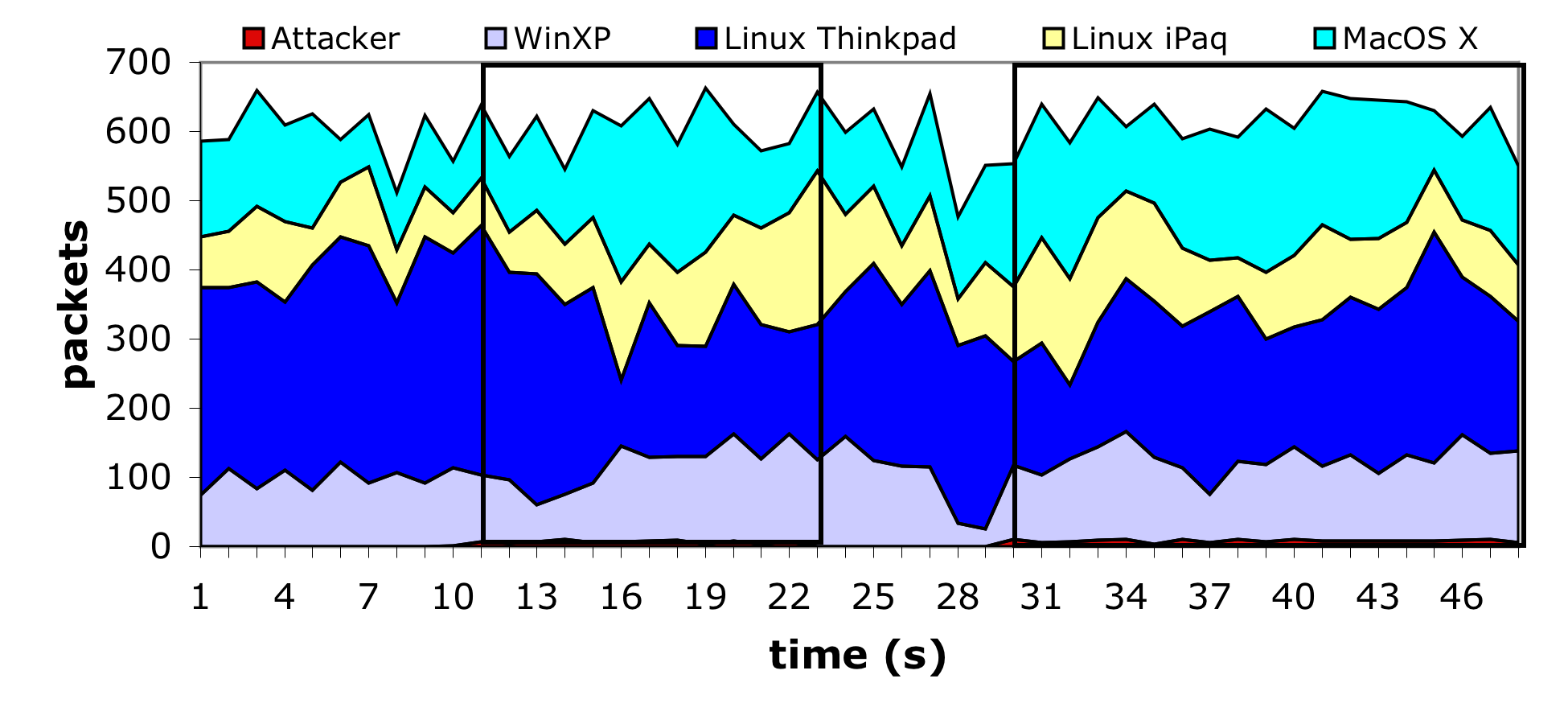

To test this defense we modified the access point used in our experiments as described above, using a timeout value of 10 seconds for each management request. We then executed the previous experiment again using the ``hardened'' access point. The equivalent results can be seen in Figure 6. From this graph it is difficult to tell that the attack is active, and the client nodes continue their activity oblivious to the misdirection being sent to the access point.

However, our proposed solution is not without drawbacks. In particular, it opens up a new vulnerability at the moment in which mobile clients roam between access points. The association message is used to determine which AP should receive packets destined for the mobile client. In certain circumstances leaving the old association established for an additional period of time may prevent the routing updates necessary to deliver packets through the new access point. Or, in the case of an adversary, the association could be kept open indefinitely by spoofing packets from the mobile client to the spoofed AP - keeping the association current. While both these situations are possible, we will argue that they are unlikely to represent a new threat in practice.

|

There are two main infrastructure configurations that support roaming. For lack of a better name we refer to these as ``intelligent'' and ``dumb''. In the ``intelligent'' configuration the access points have an explicit means of coordination. This coordination can be used to, among other things, update routes for and transfer buffered packets between access points when a mobile node changes associations. Since there is not currently a standard for this coordination function, AP's offering such capabilities typically use proprietary protocols that work only between homogenous devices. In contrast ``dumb'' access points have no explicit means of coordination and instead rely on the underlying layer-two distribution network (typically Ethernet) to reroute packets as a mobile client's MAC address appears at a new AP (and hence a new Ethernet switch port).

Intelligent infrastructures, due to their preexisting coordination, are easily modified to avoid the aforementioned problems caused by the deassociation timeout. Since the mobile node must associate with the new access point before it can transmit data, and since the access points are coordinated (either directly or through a third party), the old access point can be informed when the mobile node makes a new association. Based on this information the old access point can immediately honor the clients deauthentication request. While an attacker can spoof packets from the mobile host to create confusion, this vulnerability exists without the addition of the deferred deassociation mechanisms we have described.

Dumb infrastructures are slightly more problematic because of their lack of coordination and reliance on the underlying network topology. If that underlying topology is a broadcast medium, which is a rarity these days, there is no problem because all packets are already delivered to all access points. If the underlying topology is switched, then a protocol is used (typically a spanning tree distribution protocol) to distribute which MAC addresses are served by which ports. Existing switches already gracefully support moving a MAC address from one port to another, but have problems when one MAC address is present across multiple ports. In the non-adversarial case the mobile node will switch access points, proceed to send data using the new access point, and cease sending data through the old access point. From the switches perspective this is equivalent to a MAC switching ports. The mobile node may not receive data packets until it has sent one - allowing the switch to learn its new port - but that limitation applies regardless of the deauthentication timeout. In the adversarial case the attacking node could generate spoofed traffic designed to confuse the switch. However, this does not represent a significant new vulnerability - even without the delay on deauthentication/disassociation an attacker can spoof a packet from an mobile client in order to create this conflict (including a WEP protected packet after key recovery).

| Time | Source | Destination | Duration (ms) | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.294020 | fc:1d:e7:00:15:01 | 32767 | 802.11 CTS | |

| 1.295192 | 10.0.10.2 | 10.0.1.2 | 258 | TCP Data |

| 1.296540 | 00:03:93:ea:e7:0f | 0 | 802.11 Ack | |

| 1.297869 | 10.0.1.2 | 10.0.10.2 | 258 | TCP Data |

| 1.299084 | 00:03:93:ea:e7:0f | 0 | 802.11 Ack | |

| 1.300275 | 10.0.1.2 | 10.0.10.2 | 258 | TCP Data |

| 1.300439 | 00:03:93:ea:e7:0f | 0 | 802.11 Ack | |

| 1.302538 | fc:1d:e7:00:15:01 | 32767 | 802.11 CTS | |

| 1.306110 | fc:1d:e7:00:15:01 | 32767 | 802.11 CTS | |

| 1.309543 | 10.0.10.2 | 10.0.1.2 | 258 | TCP Ack |

| 1.309810 | 00:03:93:ea:e7:0f | 0 | 802.11 Ack | |

| 1.312237 | 10.0.1.2 | 10.0.10.2 | 258 | TCP Data |

| 1.313452 | 00:03:93:ea:e7:0f | 0 | 802.11 Ack |

Under the assumption that these bugs will be removed in future 802.11 products (since they effectively prevent RTS/CTS from working as well as the 802.11 Point Coordinator Function and all related Quality-of-Service services based on 802.11) the remainder of this section explores the NAV vulnerability in the context of the popular ns simulator (which implements the protocol faithfully).

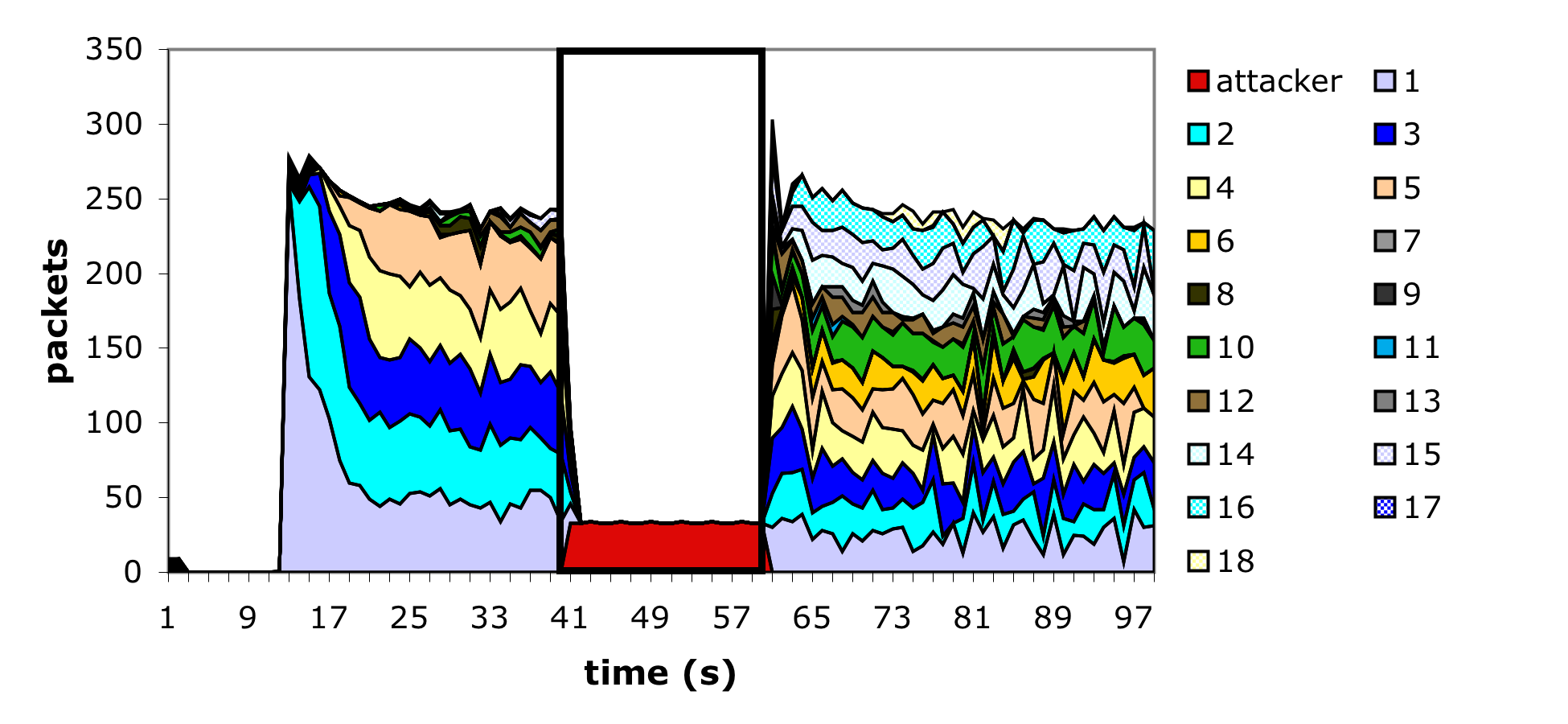

We implemented the virtual carrier-sense attack by modifying the ns [NS] 802.11 MAC layer implementation to allow arbitrary duration values to be sent periodically, 30 times a second, by the attacker. The attacker's frames were sent using the normal 802.11 access timing restrictions, which was necessary to prevent the attacker from excessively colliding with other in-flight frames (and thereby increase the amount of work required of the attacker). In addition the attacker was modified to ignore all duration values transmitted from any other node. The network topology was chosen to mimic many existing 802.11 infrastructure deployments: a single access point node, through who all traffic was being sent, 18 static client nodes and 1 static attacker node, all within radio distance of the access point. As with the previous experiments, ftp was used to generate the long-lived network traffic. We simulated attacks using ACK frames with large duration values, as well as the RTS/CTS sequence described earlier. Figure 8 shows the ACK flavor of the virtual carrier-sense attack in action, but both provided similar results: the channel is completely blocked for the duration of the attack.

|

We modified our simulation to add these limits, assuming that a value of 1500 bytes as the largest packet. While this is not strictly the largest packet that can be sent in an 802.11 network, it is the largest packet sent in practice because 802.11 networks are typically bridged to Ethernet, which has a roughly 1500 byte MTU. Figure 9 shows a simulation of this defense under the same conditions as the prior simulation. While there is still significant perturbation, many of the individual sessions are able to make successful forward progress. However, we found that simply by increasing the attacker's frequency to 90 packets per second, the network could still be shut down. This occurs because the attacker is using ACK frames, whose impact on the NAV is limited by the high cap.

To further improve upon this result requires us to abandon portions of the standard 802.11 MAC functionality. At issue is the inherent trust that nodes place in the duration value sent by other nodes. By considering the different frame types that carry duration values we can define a new interpretation of the duration that allows us to avoid most possible DoS attacks. The four key frame types that contain duration values are ACK, data, RTS, and CTS, and we consider each in turn.

Under normal circumstances the only time a ACK frame should carry a large duration value is when the ACK is part of a fragmented packet sequence. In this case the ACK is reserving the medium for the next fragment. If fragmentation is not used then there is no reason to respect the duration value contained in ACK frames. Since fragmentation is almost never used (largely due to the fact that default fragmentation thresholds significantly exceed the Ethernet MTU) removing it from operation altogether will have minimal impact on existing networks.

Like the ACK frame, the only legitimate occasion a data frame can carry a large duration value is if it is a subframe in a fragmented packet exchange. Since we have removed fragmentation from the network, we can safely ignore the duration values in all data frames.

|

The last frame to consider is the CTS frame. If a lone CTS frame is observed there are two possibilities: the CTS frame was unsolicited or the observing node is a hidden terminal. These are the only two cases possible, since if the observing node was not a hidden terminal it would have heard the original RTS frame and it would be handled accordingly. If the unsolicited CTS is addressed to a valid, in-range node, then only the valid node knows the CTS is bogus. It can prevent this attack by responding to such a CTS with a null function packet containing a zero duration value - effectively undoing the attackers channel reservation. However, if an unsolicited CTS is addressed to a nonexistent node, or a node out of radio range, this is indistinguishable from a legitimate hidden terminal. In this case, there is insufficient information for a legitimate node to act. The node issuing the CTS could be an attacker, or they may simply be responding to a legitimate RTS request that is beyond the radio range of the observer.

An imperfect approach to this final situation, is to allow each node to independently choose to ignore lone CTS packets as the fraction of time stalled on such requests increases. Since hidden terminals are a not a significant efficiency problem in most networks (as evidenced by the fact that RTS/CTS are rarely employed and since the underlying functionality does not seem to work in many implementations) setting this threshold at 30 percent, will provide normal operation in most legitimate environments, but will prevent an attacker from claiming more than a third of the bandwidth using this attack.

It should also be noted that existing 802.11 implementations use different receive and carrier-sense thresholds. The different values are such that, in an open area, the interference radius of a node is approximately double its transmit radius. In the hidden terminal case this means that although the hidden terminal can not receive the data being transmitted, it still detects a busy medium and will not generate any traffic that would interfere with the data, so the possibility of an unsolicited CTS followed by an undetectable data packet is very low.

But ultimately the only foolproof solution to this problem is to extend explicit authentication to 802.11 control packets. Each client-generated CTS packet contains an implicit claim that it was sent in response to a legitimate RTS generated by an access point. However, to prove this claim, the CTS frame must contain a fresh and cryptographically signed copy of the originating RTS. If every client shares keying material with all surrounding access points it is then possible to authenticate lone CTS requests directly. However, such a modification is a significant alternation to the existing 802.11 standard, and it is unclear if it offers sufficient benefits relative to its costs. In the meantime, the system-level defenses we have described provide reasonable degrees of protection with extremely low implementation overhead and no management burden. Should media-access based denial-of-service attacks become prevalent, these solutions could be deployed quickly with little effort.